Exclusive: Boelter Lied About Slain Missionary

Accused assassin preached a story about a slain missionary whose family is now raising doubts

I’m an independent journalist whose reporting is made possible by paid supporters. Thank you for sharing and supporting this journalism.

To hear Vance Boelter tell it, his friendship with and discipleship under a Christian missionary was such a formative experience that he named his only son after the man.

The missionary, David Emerson, was killed in Zimbabwe in 1987. Boelter now stands accused of shooting two Minnesota lawmakers and their spouses, allegedly targeting Democratic politicians and other advocates of reproductive rights.

Emerson’s brother tells me that Boelter’s alleged actions are the farthest thing from what their slain brother believed and taught. And the Emersons’ account adds serious doubts to other inconsistencies in Boelter’s story about David.

As I’ve written before, contrasting Boelter’s religious speeches with the realities of his business fortunes — or lack thereof — reveals a man willing to inflate the stories he told in both worlds.

In fact, neither his resume nor public accounts since he was identified include the fact, not previously reported, that Boelter apparently pursued an undergraduate degree right after high school and either failed or gave up. (His public defender did not respond to my email.)

Boelter alludes vaguely to that period in delivering the fullest known account about his relationship with David Emerson in a Sept. 26, 2021, sermon delivered in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

According to Boelter’s story, he met David in 1986 and the two were friends for more than a year prior to David’s 1987 flight to Zimbabwe. Boelter’s timeline, however, conflicts with what we know about his own life, and with what David’s brother Peter shared with me over the past week.

The Timeline

Boelter begins his story about David by telling the DRC congregants, “In school, I went to college and I met a believer who discipled me and taught me much about Jesus.”

It’s not clear why he stumbles, giving us the awkward phrase, “In school, I went to college…” But there’s no public record of him beginning higher education until 1988, a year after David was killed.

Boelter graduated from Sleepy Eye High School in Minnesota in 1985. There’s been no reporting until now on those three formative years in between. And news reports said he didn’t get his undergraduate degree, from St. Cloud State University, until 1996.

But St. Cloud State is just two hours from Sleepy Eye, MN, Boelter’s hometown. So, after Peter Emerson told me that his brother stayed in St. Cloud, MN, in the first half of 1987, I emailed St. Cloud State to ask whether Boelter might have begun his studies there right after high school.

It turns out, he did. Here’s the full statement from St. Cloud State spokesperson Zach Dwyer:

“Vance Boelter graduated from St. Cloud State University in 1996 with a bachelor of elective studies degree in international relations. He first attended SCSU between 1985-88, later returning from 1994-96 and graduating in winter of 1996.”

As the New York Times reported, Boelter began a two-year program at the Christ for the Nations Institute in 1988. Why he left St. Cloud State three years into a four-year program, we don’t know.

Boelter’s life story is full of embellishment and hyperbole in sharp contrast with a reality marked by failed ambitions, professional stagnation, and, ultimately, financial hardship. So maybe St. Cloud State was just another wash-out, one Boelter wouldn’t rectify until almost a decade later when he finally finished his degree.

Boelter switched from St. Cloud State to a notoriously evangelical, even radically Christian institution. It raises the possibility that David Emerson’s death the year before inspired a switch in Boelter’s life focus.

But Boelter’s religiosity had him in its grip years before he met David. He surrendered to Jesus at the age of 17, his ascetic new truth moving him to live in a tent on his lawn even before he finished high school.

And if Boelter’s newly revealed first stab at an undergraduate degree did put him in proximity with David Emerson, it still doesn’t address other inconsistencies in his account. For one thing, it’s not possible they knew each other as long as Boelter says in his sermon:

“About a year later, after I’d met him, he told me, he was so excited, he said, ‘I’m going to Africa. I’m going with a ministry and we’re gonna dig wells for people because they need good water. And then we’ll share the Gospel.’”

As Peter Emerson pointed out, Boelter’s account makes it sound as if David were heading to Africa for the first time. In fact, David had already been in Zimbabwe for more than two years, from July 1984 through late 1986.

David only came home because his visa expired — meaning his return to Zimbabwe wouldn’t be some grand new adventure, but simply picking up where he left off.

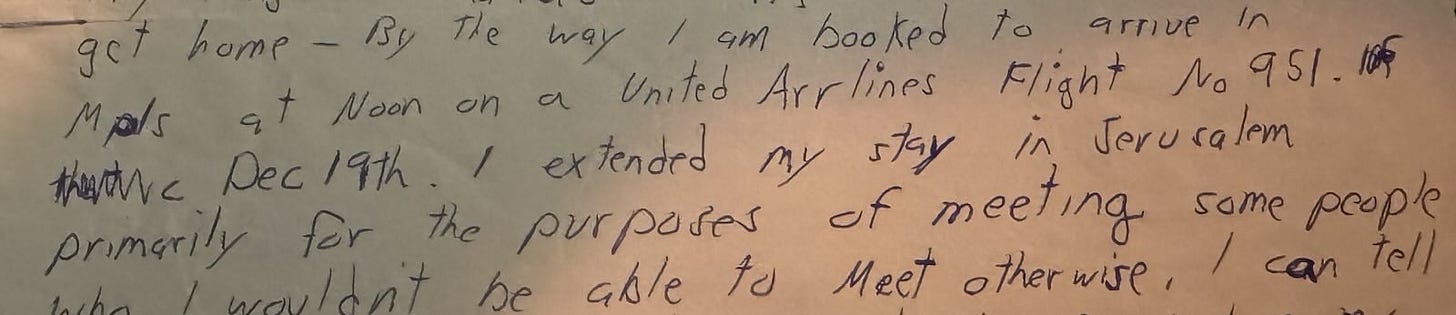

And Boelter couldn’t have met David “about a year” before announcing his return to Zimbabwe. That’s because David didn’t return to Minnesota until Dec. 19, 1986, and didn’t arrive in St. Cloud until after Christmas, to visit and then stay with his sister. He returned to Zimbabwe around June 1987.

Which means the time between David meeting Boelter and actually leaving for Zimbabwe, let alone announcing the trip, could have been only about six months, maximum.

Boelter said that during David’s second stint in Zimbabwe, “He sent me letters.” This would have been approximately June 1987 through David’s murder on Nov. 25, 1987.

Peter Emerson can’t rule out the possibility that that’s true, but the family kept David’s correspondence and there are no communications from Boelter. In fact, Peter found no references to Boelter whatsoever in David’s papers. (Whatever possessions David had in Zimbabwe, including any correspondence, were burned by his killers.)

Is it possible Boelter met David Emerson during those six months? It is. David was driving a bus at the time and involved with his church in St. Cloud.

Is it possible David would have done something like discipling Boelter? “It sounds exactly like something he would do,” Peter Emerson told me, though he’s skeptical at best. Most of the family doesn’t believe it, but the sister, the one David stayed with in St. Cloud, does.

“I think she really wants to believe in Dave reaching out,” Peter said. “She likes that and she sees it as a good thing.”

And there’s no reason to think it wouldn’t have been. As I wrote last week, there’s a disturbing possibility that even mainstream religious beliefs created in Boelter a cognitive tension with the realities of capitalist America.

However David might have discipled Boelter, it apparently wouldn’t have been political. At the time, even Pentecostal, evangelical churches in America were largely non-political.

That was true of David’s church, too, Peter told me. And of David.

“His church did not want to be political,” Peter said. “They just wanted to spread the word of Jesus,” he explained.

“And Dave, I didn’t see him doing anything political,” Peter said. Nothing to say about abortion or LGBTQ+ people. No embrace of radical, or even allegorically violent theology like that which Boelter would later encounter at Christ for the Nations.

Even as a devout Christian, David harbored no animosity toward Muslims. He stayed with a Muslim family in Israel on his way home in 1987, sharing with the Emersons his admiration for their culture of hospitality and strong family bonds.

The Emersons were uniformly Democratic, capital D. If anything, before David joined his church, “He was a bit of a communist,” Peter said.

Boelter doesn’t mention that, or say anything about David’s politics, even though his 2023 sermons lament American churches not condemning abortion, and people rejecting his gender-identity norms.

Boelter’s description of David’s life and death in Zimbabwe also includes information that’s either not backed up by any other source, or is directly contradicted by other accounts.

Life in Zimbabwe

According to Boelter, David said, “I’m going with a ministry and we’re gonna dig wells for people because they need good water.”

It’s not impossible that the missionary community dug wells, but if they did, it was an incidental aspect of their project. The idea was to operate a farm responsibly, teaching locals how to rotate crops and sustain the land’s arability.

If anything, Peter Emerson says, the big project at the time was a dam. However religious the framework, the overall mission was to serve the people of Zimbabwe. Known as the Communities of Reconciliation, they hoped to reconcile the splits between Black and white people, at home and in Zimbabwe, where their residential rooms had one Black roommate and one white.

Whatever David discussed doing in Zimbabwe, it likely wouldn’t have been in the future tense. He’d already been there for more than two years and his work there was well under way. He was planning to make a life there, to raise a family with a fellow missionary he met in Zimbabwe.

News accounts of the massacre referred to the community teaching local farmers modern techniques.

There were two farms, New Adams and Olive Tree. Neither one had the security measures typical of other white-owned farms in Zimbabwe. The nation was navigating a sometimes violent transition away from white control.

As part of that transition, the new Zimbabwe government allowed white farmers to keep land they owned under the white regime. Most of them had fences and barbed wire and hired security as defenses against resentful Zimbabweans. But not New Adams and Olive Tree.

Boelter explained why. According to him, David didn’t want any non-Christian attackers to get killed and be damned for eternity because they hadn’t found Jesus first.

Boelter said, “My friend didn’t believe in guards or security, because, he said, if somebody comes and they don’t know God, and they get killed by security, they’re lost.”

It’s a puzzling explanation on its face, because a mere fence was unlikely to send anyone to Hell. But it also doesn’t gibe with what community leaders said publicly at the time, or what Peter told me.

For one thing, security measures weren’t David’s decision. He didn’t found the community, which was started two years before he got there, so it wasn’t his reasoning that drove the security decisions.

The farms lacked security because the missionaries who started them didn’t want to imply that God wasn’t watching over them. As Peter pointed out, the reason for creating the community was to teach and minister to people there — tough to pull off if you’re keeping them away at gunpoint across barbed wire.

And Boelter’s claims about the murder itself are even more difficult to reconcile with reality.

The Massacre

The attackers struck silently, targeting the white farmers. No guns to alert anyone nearby. First they hit the New Adams farm. Then they moved on to Olive Tree, where David lived.

The attackers bound their hands: Barbed wire. Then murdered their victims with machetes. No longer concerned about drawing attention, they torched Olive Tree.

Whatever remains were left were buried later in the area.

Explaining the massacre, Boelter claimed in his 2021 sermon that “people didn’t want them [the missionaries] in the area so they lied about ‘em, they said they were Communists.”

There’s no evidence of this in the public record. Peter Emerson never heard it before. And it’s in direct conflict with the facts.

The killers themselves were Communists. They left a note calling the dead missionaries capitalists and demanding the expulsion of westerners.

The Washington Post quoted a Zimbabwe official who had seen the note and said the intent of the killers was to “drive western capitalist-oriented people out of the country.”

A report by Prairie Public Broadcasting about a remembrance for one of the victims said that the missionaries had complained about Zimbabwean squatters. The government, the report said, had run the squatters off the farm. The suggestion is that the squatters got the Marxist-Leninist dissidents to raid the farms for revenge.

Peter Emerson told me the squatters were nomads who didn’t know how to farm the land and moved on after reaping their harvest, ruining the soil for new crops.

A 1989 report seems to support the story that squatters got a handful of dissident rebels to carry out their vendetta against the missionaries. The Los Angeles Times reported that the killers were caught — seven dissidents and eight squatters. (They were released after a court ruled that a 1988 amnesty declared by Pres. Robert Mugabe applied to the killers, too.)

Is it possible David in one of the letters he supposedly sent Boelter shared an erroneous rumor that someone local was calling them Communists? Perhaps, but even in that scenario, it would be odd if Boelter never changed his narrative to account for the facts that came out afterward.

Is it possible Boelter simply made it up? It wouldn’t be his first fabrication. As I reported last week, Boelter claimed to be working with hundreds of farmers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with 1,000 women raring to start work as motorcycle taxi drivers.

And a letter found in Boelter’s car after the Minnesota shootings alleged that Gov. Tim Walz (D-MN) was in on it, and wanted Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) dead to clear Walz’s path to a Senate run. Boelter making shit up appears not to be out of the question.

He botches other details about the massacre, as well, saying two children survived by hiding. That’s not what contemporary reports said. One fled, and one was spared to tell what she had seen and share the note the killers left with her.

Of course, it’s unreasonable to expect someone to get all the details right several decades later. Except that the reason Boelter tells this story is to illustrate just how important David Emerson supposedly was and still is to him.

David’s death illustrates Boelter’s theme that belief in Jesus does not guarantee an easy life. Boelter says David left such an impression that after David’s murder he promised God he would name his son after David. He had four daughters — Grace, Faith, Hope, and Joy. And one son: David Emerson Boelter.

The Second Massacre

Boelter has not been convicted in a court of law, but the evidence against him suggests that some toxic stew of convictions — religious, political, or both — drove him to plan and partially carry out a massacre of his own.

Media accounts of Boelter’s past included his story about David Emerson. For obvious reasons, this has caused new pain for David’s siblings.

The Minnesota killings, of course, shocked even a nation somewhat inured to political violence. Peter Emerson tracked the story.

“I was already following this guy, because I’m from Minnesota and I’m a Democrat — or at least not a Republican — and felt it was horrific, and then I read the story, and there’s my brother’s name,” Peter said. “It’s disturbing to see … forty years later, having it pop up again, from such a horrible person.”

After David’s murder, the Emersons got letters from people testifying to the impact even a brief encounter with David had had on them. “[A] profound experience with him in a simple 2 hour hitchhiking ride,” Peter said.

So it’s possible, Peter allows, that Boelter was one of those people. Profoundly affected by a brief encounter. Then moved by David’s death, which was national news. Perhaps so moved that the story grew in Boelter’s mind.

Peter’s theory is that Boelter heard David’s story through David’s church in St. Cloud. They made a big deal about the massacre, even producing a play as a sort of theatrical hagiography.

Did Boelter hear the story from the church? Or see their play? And consciously or not weave into his own story? Or did he, as with his business ventures, inflate a tiny seed or aspiration into a narrative that connected him, Boelter, to one of the creation stories of his faith?

Either way, Boelter’s sermon means that David’s death is becoming known again, but this time as a chapter not in David’s story but in the story of a man accused of horrific acts. Boelter’s self-mythologizing threatens to tie the two together, if not in fact, then in the ruination that religious zealotry has brought to two lives. One a victim. One, allegedly, a perpetrator.

Ironically, the two men have something else in common. Both spent part of their high-school years living in tents. While Boelter was driven there by religion, however, David Emerson was inspired by his interest in Native American crafts to build a teepee in his yard. “He was almost an Eagle Scout,” Peter said.

Later, David would build canoes and even cabins, ultimately putting those skills to use building a community of western missionaries and Zimbabwe farmers, living and working side by side. Reconciliation.

But it wasn’t religion that first drew David Emerson to the church that brought him to Zimbabwe. He had become frustrated with his life, drinking too much and getting into bar fights. That may have spurred his interest in religion, but mostly it was a woman in the church. David fell for her.

The feelings were never reciprocated, but the church welcomed him. In fact, it treated him like family. Over his own family, Peter said.

David became a proselytizer, judgmental. The church’s teachings created tensions in the family. So did its religious fervor.

“Most of us were kind of uncomfortable with that church,” Peter said. “It was too crazy, and it was cult-like, we felt.”

So when David contemplated a new life in Zimbabwe, their father had real concerns.

The church itself was one of them. But so was the danger. (David and Peter’s Dad died just a couple years after David’s murder, Peter said. “Broken-hearted.”)

The Emersons will likely fade from the public eye as Boelter does, without any of us knowing for sure whether and how David’s path really intersected with Boelter’s. Even if Boelter speaks out about it, there’s scarce reason to give him any credence.

The legacy of David and his family may end up simply being that they came forward. Serving as witness to the truth. Testifying that the man now facing possible trial — for a cold-blooded political assassination and shooting spree — had a history spanning decades of inflating and embellishing.

As we’ve been talking over the past week, I’ve been sharing some of my research with Peter. He told me he wants to learn about the church that took his brother, and about where David might be buried, so he can visit the gravesite.

He wants to know the truth. And to say goodbye.

I’m a veteran journalist and TV news producer who’s worked at MSNBC — as co-creator of Up w/ Chris Hayes and senior producer for Countdown with Keith Olbermann — CNN, ABCNews, The Daily Show, Air America Radio, and TYT. My original reporting on Substack is made possible by a handful of paid subscribers. Thank you.

Wow! This is a powerful and moving piece with multiple layers. Excellent work, Jonathan! Won’t see this attention to detail anywhere else. Funny how in America—a supposedly secular country—if you claim that you’re doing something for religious (i.e. “Christian) purposes you don’t get questioned.

I'm adding the Emerson family to Boelter's body count. This story keeps getting worse.